The beautiful gain: what can Brazilian football tell us about the effect of non-compete clauses on wages?

With the 1998 Pelé Law eliminating transfer fees for players whose contracts had expired, Brazilian football provides an ideal setting to test the effect of non-compete agreements on wages. This analysis reveals that older players gained the most, whereas the wages of young players fell, which has wider implications for policies on the use of non-competes amongst low- and high-income employees, write Bernardo Guimarães, João Paulo Pessoa, and Vladimir Ponczek (all Sao Paulo School of Economics-FGV).

Non-compete agreements, which temporarily prevent employees from entering into competition with their current employer once they leave, make it impossible – or at least very costly – for many employees to accept job offers in similar fields, firms, or markets. It has been estimated that 18% of all US workers are currently bound by non-compete agreements. This figure rises to 39% for those with a professional degree and to 46% for those earning over USD 150 thousand a year.

This sheer prevalence has recently seen non-compete agreements become an important policy issue. Towards the end of 2020, for instance, the UK government launched a public consultation about a possible ban on non-compete clauses.

The effects of non-compete clauses are theoretically mixed. On the one hand, they might be beneficial for strategic reasons, such as protecting trade secrets. On the other, they might adversely affect wages. Moreover, by imposing costs on labour mobility, non-compete agreements could hinder the efficient matching-up of employers and employees. But how important are these effects? Surprisingly, football might well provide an answer.

How do non-compete causes relate to Brazilian and world football?

Generally, the labour market for footballers involves transfer fees. In August 2020, for example, Lionel Messi made public his intention to leave FC Barcelona. But since his contract was due to expire in 2021, a rival club would have had to pay a £630 million fine to sign Messi. Since no club was willing to pay such an astronomical sum, Messi decided to stay one more year and (potentially) leave Barcelona for nothing at the end of his contract.

Though now a common feature in the market for professional footballers, moving freely at the end of a contract was not always an option. Until 1995, clubs in the European Union could demand transfer fees even after the contract had expired. It was only when the Belgian midfielder Jean-Marc Bosman successfully challenged the legality of this state of affairs via the European Court of Justice that football changed forever.

In Brazil, meanwhile, legal arrangements between players and clubs remained as they had been in Europe prior to the Bosman Ruling. This changed in 1998 with the Pelé Law, named for the great Brazilian player and then Minister of Sports who had been a leading light of the campaign for a ban on non-competes. After the new law came into force, teams could still include clauses demanding transfer fees for players, but only during the term of their contracts.

How do non-compete agreements affect labour markets?

In a recent discussion paper, we explore this policy change in Brazil to study how non-compete agreements affect wages and efficiency in the labour market. Brazilian football constitutes a particularly appropriate context for studying how non-compete agreements affect wages and efficiency for a couple of key reasons. First, because the end of non-compete clauses was an exogenous policy change. And second, because the new law had an important effect on the labour market for first-class professional footballers but virtually no impact on the economy as a whole. With there being few occupational switches between football and other professions, labour market policies and economic shocks affecting other sectors are not a major source of concern.

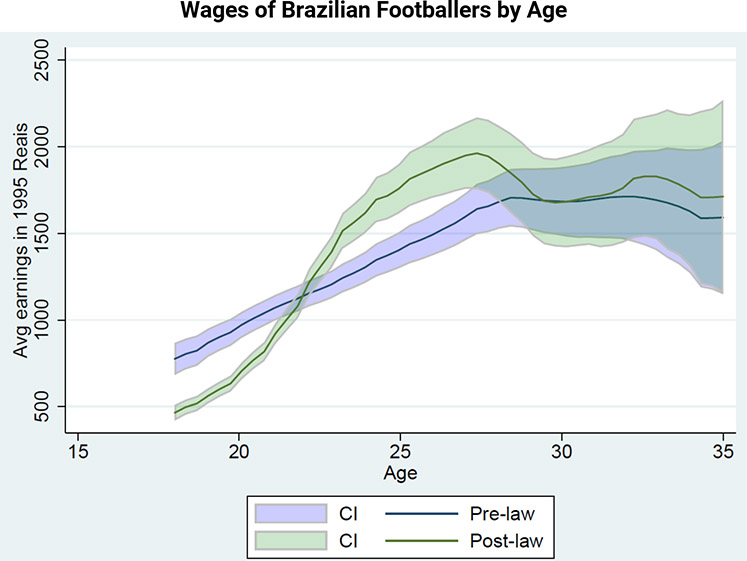

The figure below shows how the new law affected the wages of Brazilian footballers. It shows the estimated relationship between wages and age in the two years just before and just after the Pelé Law, controlling for player fixed effects. The shaded areas are the respective 95% confidence intervals. We can see that players’ lifetime income increased in the years following introduction of the new law, but the age-earnings profile changed. Players at age around 28 gained the most, but the wages of young players fell.

Understanding changes in wages after the Pelé Law

What is behind this change in the age-earnings profile? It could be a distributional effect: the law could have raised players’ bargaining power. Alternatively, it could be an efficiency effect: by removing barriers to transfers, it could have improved the allocation of players to clubs – for example, making it easier for clubs to hire players that are a good fit with the squad. Both mechanisms could be at play, but what is making the difference?

In order to separate distributional and efficiency effects, we propose an economic model and use a rich dataset to explore the effects of the Pelé Law. The model captures the main elements of the rich contractual environment of labour markets for professional athletes and some other high-paid occupations: long-term contracts, transfer fees, uncertainty about players’ performances, and auctions to sign players when contracts expire. The auction requires the payment of a fee to the owner club when non-compete clauses are in place, while no fee is required in the absence of non-competes.

We estimate the model parameters to match the wage profile and turnover from the post Pelé Law period. We then show that introducing non-compete clauses in labour contracts in the model changes the wage as in the data: a player’s lifetime income goes down with non-compete frictions, but the salary for young players rises.

From the model, we can ascertain the quality of the matches between players and clubs, both with and without non-compete agreements. We find that the average match quality goes up slightly with the Pelé Law. However, this effect is minimal and accounts for less than 1% of the increase in players’ lifetime income.

The distributional effect of non-compete agreements

Overall, the negative impact of non-compete agreements on match efficiency is positive but very small. The distributional effect, however, is very large.

The main driver of the effects on wages is the auction between clubs after an agreement expires. In a situation with non-compete agreements, the current club gets a fee if it loses the auction, paid by the winning club. Hence, both clubs have incentives to bid less for the player. This substantially reduces player wages. This channel is likely to operate in other settings, though more research is needed to assess the external validity of our findings.

With the above caveat in mind, the paper has implications for the policy debate. For low-paid workers, the effects on wages are very important. For high-paid workers, distributional concerns are less relevant, and efficiency issues are crucial. In particular, match efficiency is a key consideration. Hence, the paper provides support for restrictions on non-competes for low-income workers but not for high-paid employees.

This article was originally published by LSE Latin America and Caribbean Centre

- The beautiful gain: what can Brazilian football tell us about the effect of non-compete clauses on wages? - June 17, 2021

- The Best Young Brazilian Footballers Right Now - March 10, 2021

- Pele gets COVID vaccine, urges social responsibility - March 3, 2021